The Unique tradition of political violence

Oct 24, 2025 - By Ashutosh Roy Politics

Bengal’s Endless Cycle of Blood and Power

Violence and strife have plagued Bengali politics since independence besides its glittering patriotism and cultural legacy. Perhaps, West Bengal could never forget the deep seeded pain of losing loved once during the almost illogical and radical partition. So, the political violence has become a part and parcel of West Bengal.

On top of it, the migration and infiltration problems have been continuously troubling the state’s demographic structure, so as political violence. Thus, the same tradition has been continuing even today under the leadership of Mamata Banerjee. So, Let’s have a quick review of the past.

The recurring waves of migration and infiltration have continued to unsettle its demography and fuel political anxieties. Under Bengal’s rich culture lies a long history of political violence that has lasted beyond different ideologies and parties.

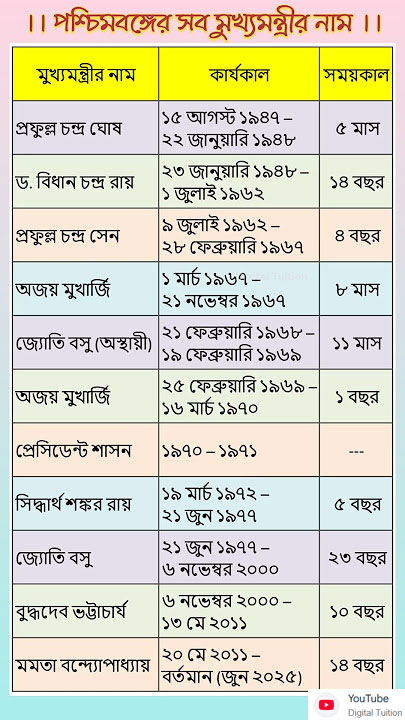

Perhaps none of the Chief Minister can claim that his regime had been an era without political violence. Even today, the migration and infiltration remains as a serious concern often leading to political rifts.

Bidhan Roy’s Paradox and Political Violence

Refugee influx and refugee movements had been the two cornerstones during the regime of Dr. Bidhan Chandra Roy, who really envisioned Bengal in the long term. The Salt Lake City, Durgapur, Kalyani are his brainchild only.

The 1959 protest against the widespread food shortages and price hikes and the deadly police crackdown on the protestors resulted around 80 casualties. In 1953, a month-long movement began against a small, one-paisa increase in the tram fare.

A major teachers’ protest in 1954 also saw police confrontation and violence. The British-trained Kolkata Police, including the mounted unit, brutally cracked down on demonstrators during this period.

Analysts may raise acrimonious debate whether the political violence of this era was a turning point in West Bengal’s history. The fact remains, Bengal had already grown accustomed to political violence during that period

The 1960s: When Hunger Met Rebellion

A country-wide drought led to Food scarcity and civil unrest in 1966 in West Bengal also. The brazen and ruthless police brutality became evident when police in Basirhat opened fire on students protesting the scarcity of rations and kerosene, killing a school student, Nurul Islam.

The killing incited a spontaneous and widespread state-wide movement that lasted for over a month and a half. The trigger-happy police had cracked down heavily on protestors, causing a large number of casualties.

Rise of Naxalites in 1967 and the ruler’s shameless and brutal exploitation of police caused bloodbath across the state. In this period, a heightened political rivalry saw a bloody turf war between the party cadres. The political violence between Congress and communist cadres became widespread and unfortunately even today, we are carrying the same legacy.

1967–1972: Instability and Infamy caused political violence

The flip-fop governments and impose of President rules several times in West Bengal have marred the period 1967 to 1972. Perhaps the abolition of the Legislative Council had been the only success of the United Front government. Political instability spreads its ripple effects, often causing bloodshed.

The Ajay Mukherjee–Jyoti Basu government was no exception.

Then came the 1972 election, arguably the darkest in Bengal’s democratic history. Rampant booth capturing, intimidation, and rigging turned democracy into a mockery. The people voted, but the outcome was already written.

The Black Years of Siddhartha Shankar Roy

Siddhartha Shankar Roy’s precise rein of five years is known as the blackspot in West Bengal’s political democracy. The ruthless and indiscriminate slaughter of Naxalites had become the trademark of that era.

The brightest students from many colleges and universities became victims of brutal police violence. This included students from Presidency College and Jadavpur University. CPI (ML) and other communist parties became victims of extra-judicial killings. Shameless police carried out those killings under the administration’s orders. The widespread news is that Siddhartha Shankar, as Chief Minister of West Bengal, ended the Naxalite menace.

The congress rewarded him for his brutality and appointed him Governor of violence-ridden Punjab in 1986. In Punjab, he earned praise for his proactive role in confronting the Khalistani insurgency.

The Left Front’s Red Stains

The left front stormed into the power in 1977 with a clear mandate. They raised a a lot of expectation in the minds of commoners, mainly in rural belt. They worked excellent with a coalition Government at the initial stage. But the arrogance of power slowly yet surely consumes everyone.

They forget their experience of being oppressed and the pain of staying in the opposition. Gradually, comfort and luxury overwhelm them. Then they, too, begin to oppress others.

If one looks at West Bengal, the one and only Jyoti Basu heralded a new era in the regime of coalition Government.

In contrast, the Left Front government forcibly evicted thousands of refugees from the Marichjhapi island in the Sundarbans in 1979. The ruthless police firing claimed a lot of lives. A mob of CPI(M) workers in 1989, allegedly vandalized the house of a Congress municipal chairman, killing his two brothers.

On July 21, 1993, Kolkata police fired on a Youth Congress protest march led by Mamata Banerjee, killing 13 people. Trinamool Congress still leverage the benefits of brutality of Jyoti Basu Government in the name of Martyrs Day. Though Congress can claim its copyright.

The mystery remains unraveled. The procession for epic-cards somehow diverted to the State Headquarters, Writers’ Building, instead of the Election Commission office.

In Birbhum district, 11 landless Muslim laborers were lynched by CPI(M) cadres in 2000 for supporting an opposition party. CPI(M) workers allegedly burned alive 11 Trinamool Congress supporters in Chhoto Angaria village in 2001.

Singur violence (2006) and Nandigram Massacre (2007) have become landmarks for eviction of the Left regime and bring Mamata Banerjee to power. Just before the 2011 state elections, CPI(M) cadres reportedly fired indiscriminately from a party camp in Netai village, killing nine people.

Mamata Banerjee’s Autocratic Democracy

The shameless usage of administration and police to stop oppositions has earmarked The Mamata Banerjee regime. It may be in the way of vandalization or using money or muscle power. Bengal has hardly seen a government ever-so-keen on gagging the opposition as they are intolerant to any dissent tone. The oppositions don’t get any space for meeting or demonstration. They are to approach the court to seek permission.

Perhaps Mamata Banerjee has portrayed the best example of electoral autocracy, where she has been continuously holding the chair for fifteen years through democratic election processes.

Political Violence: The Unbroken Legacy

West Bengal has watched the party-led democracy during the regime of CPM and now completely fail to isolate the party from the administration.

Mamata Banerjee, the key portfolio holder in both party and administration has been ruling the state by her own whims and thoughts. If the Administration can’t be isolated from the party, it will only reach us to a bizarre state of affairs.

Her devastating desperation towards politics without the pesky inconvenience of an opposition may mark her tenure will go down in history as a pitch-black chapter.

The faces have changed, but the political violence endures. And until Bengal learns to separate politics from power, and dissent from disloyalty, the cycle will continue; endlessly, bloodily, predictably. Providence will smile in secret.

[…] embarrassment but as a moral reckoning. The desecration of a goddess’s idol is more than a law-and-order issue; it is an attack on Bengal’s cultural sanctity. Justice must not be confined to an arrest or a […]

[…] game of the roaring arch-rivalries and the growing anxieties over SIR can cause another set of political violence in West […]

[…] impassioned rhetoric might make the crowd on its feet, but question arises about its future. Today, political violence, groupism, criminality, communalism have become so evident, that people fear. The state has never […]

[…] to filter out news from the camouflaging views. Hence, political rows erupt, which in turn brings political violence, triggering […]